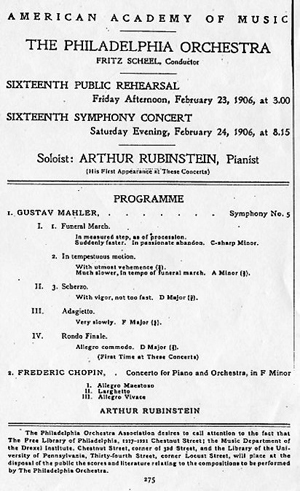

In October 1964 Hermann Scherchen conducted the Philadelphia Orchestra in a series performances of the Fifth Symphony by Gustav Mahler. (A live recording from the October 30, 1964 performance is available on Tahra CD TAH 422. Regrettably, the extensive horn solos in the third movement suffered extensive cuts.) Remarkably this was the first performance by the Philadelphia Orchestra of Mahler 5 but not the first performance in Philadelphia. In its February 2, 3, 9, and 10, 1906 printed programs The Philadelphia Orchestra announced that it would be performing the symphony later in the same month. The announcement also stated that Mahler is a "modern of moderns. He may not be a genius in the positive sense of the word but he possesses extraordinary ability in painting other people's ideas in glowing and original colors. It is claimed that his orchestration is 'the ideal of tonal gluttony; it is fascinating, magnetic, seductive. As to orchestral coloring and euphony, his scores are unequaled by any living composer.' As for demands upon the virtuosity of an orchestra - well, Mahler out-Strausses Strauss." |

Philadelphia Orchestra Program announcement February 2, 1906 |

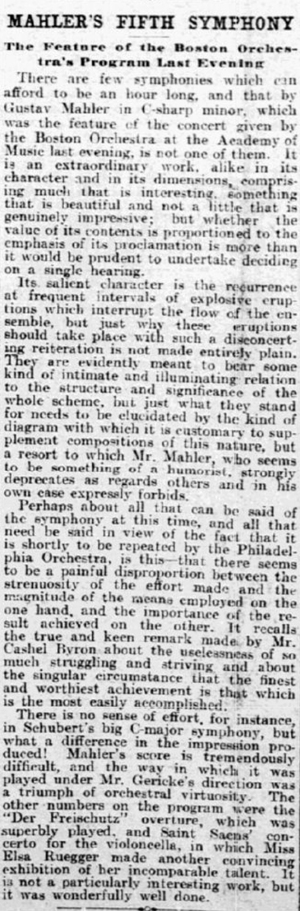

Coincidentally, that same month the Boston Symphony Orchestra was also performing Mahler 5, in Boston, New York, and Philadelphia. The principal horn player in Boston at the time was Max Hess, who had performed the solo part in the symphony's premier in Cologne, Germany on October 18, 1904 conducted by the composer. A student of Friedrich Gumpert, he had been offered the principal horn positions in both London and Boston, and had chosen the latter. By yet another coincidence, Philadelphia's principal horn was Anton Horner, who also had been a student of Friedrich Gumpert. Now it appeared that there would be the opportunity to hear both of these great orchestras and their equally great principal horn players perform this monumental symphony in the same city and the same month! The Philadephia Inquirer's review of the symphony of the February 12 performance by the B.S.O., however, was less than entusiastic: |

|

|

Philadelphia Inquirer February 13, 1906 |

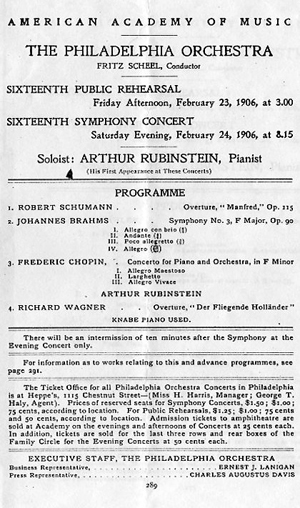

Perhaps the demands upon the virtuosity of the Philadelphians was a little more than they could handle, and they didn't want to risk unfavorable comparison with their Boston colleagues. More likely after the above review, ticket sales for their upcoming performance of Mahler 5 less than two weeks following were less than could be tolerated. Whatever the reason the actual program for February 23-24 shows that the Mahler was replaced by Schumann's Manfred Overture, Wagner's Flying Dutchman Overture and Brahm's Third Symphony. If they had played Mahler 5, as announced, then of course Anton Horner would have played the solo part. As it turned out it appears that Mr. Horner never did get to play it in his long and distinguished career. The privilege of the first Philadelphia Orchestra performance was left for his student, Mason Jones. Perhaps it would have been different if Max Hess had gone to London instead. Ironically, Horner had been offered the job in Boston before Hess, but had decided to remain in Philadelphia instead. |

Philadelphia Orchestra Program, February 23-24, 1906 |

|

Max Hess Albert Hackebarth William Gebhart F. Hain Heinrich Lorbeer Schumann (A/U) Phair (Assoc.) |

Anton Horner Joseph Horner Otto Henneberg Albert Riese |