1919 - 2009

|

I purchased the above photo in February 2008 for my personal collection. It apparently had come from the estate of Mr. Cornelius Gall who had been Mr. Jones' teacher in his hometown of Hamilton, New York. I soon realized that it really should be returned to Mr. Jones as a family heirloom so I phoned him and invited myself to visit him in July, 2008. I was very pleased that he still remembered me even though I had had only a few lessons with him when I was a teenager. He had very graciously taken time from his family while vacationing a couple of summers in Hamilton. (Many years later I also played backup for his performance of Strauss 1 with the Trenton, NJ, Symphony and had seen him from time to time at Philadelphia Orchestra concerts.) My wife, Laura, and I had a very pleasant visit at his home for nearly two hours. He was in very fine spirits and good health as he told us many stories. He showed us his two beautiful natural horns and what appeaered to be a large-bore trompe in D that he used as a natural horn on his recording of the Mozart conerto in D, K. 412/386b. In addition he showed us his massive collection of Philadelphia Orchestra recordings. He told us that Columbia and later RCA presented him with a copy of every recording on which he had played. A few months later on the evening of February 18, 2009 we happened to be on a tour of the Curtis Institute where Mr. Jones had taught for many years. Of course his long teaching career there was topic of conversation but it wasn't until the next day that we learned he had passed away that same evening. I was so disappointed that we lost him only a few months short of achieving his ninetieth birthday. [Dick Martz] |

In the Spring of 1937, Boris Goldovsky was tasked with conducting a concert by the student orchestra of The Curtis Institute of Music. Fritz Reiner was then director of Curtis but was away in London. Goldovsky, a recent graduate of Curtis himself, was Reiner's assistant. He recounts a decision he had to make Reiner's absence:Mendelssohns Midsummer Nights Dream confronted us with a problem of a different order. The Nocturne movement of this composition is famous for its beautiful French horn solo - one of the most demanding in the horn players repertoire. Now as ill luck would have it, the student who was to play this particular solo with the Curtis orchestra came down with appendicitis and had to be rushed to the hospital one week before the concert. |

During World War II Mr. Jones was a member of the United States Marine Band from 1942 to 1946. In the above photos he is seen as a featured soloist in a performance of Liszt's Les Préludes in a Marine Corps recruiting film from 1942. Note: the horn he is playing is a Kruspe "Horner Model" but it is not the same one that he used for his entire career with the Philadelphia Orchestra. |

Here are some excerpts of Mason's playing: |

The above photo appeared on April 30, 1957 with the following caption: "First Horn / Mason Jones, first horn of the six-man horn section is one of the outstanding musicians who will be heard when the Philadelphia Orchestra plays in Denver on May 19 in the auditorium arena under the baton of Eugene Ormandy." |

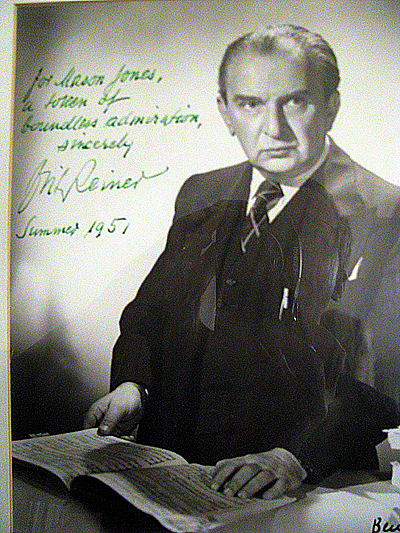

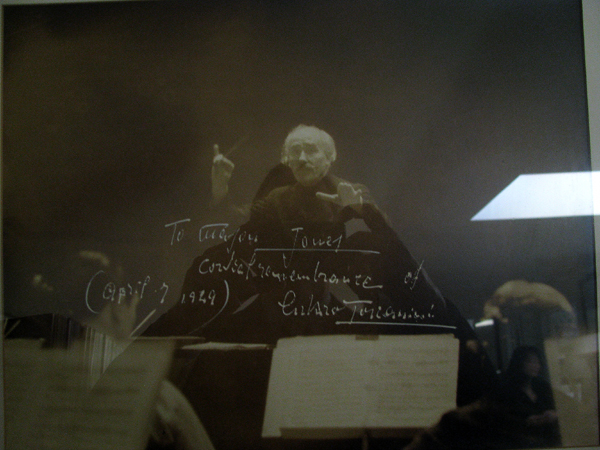

The photos below were taken by Randy Gardner who for many years had been second horn next to Mr. Jones in the Philadelphia Orchestra. Randy had visited Mr. Jones in May, 2008 while in Philadelphia to perform once again with the Orchestra. In order to better understand how to conduct strings, Mr. Jones had taken violin lessons. Now in his later years he turned to the violin as a musical outlet for his own enjoyment. Below he proudly displays one of his natural horns. At the bottom of the page are tributes from Fritz Reiner, who was once dean of Curtis Institute, and Arturo Toscanini.     For a summary of Mr. Jones' career please see the on-line article by the International Horn Society as well as the biographies referenced in the Society's magazine, The Horn Call. |